Historic Mining on Isle Royale

History

By: Lawrence Rakestraw

Download Map: JPEG (11.0MB) | PDF (4.51MB)

ining frontiers in the United States have followed a common pattern. Historically, they have been important in that they often brought the first permanent white population to isolated or uninviting areas. They have typically begun by a discovery or rumors of precious metal. Mining of a simple type led to the establishment of settlements, roads, and other facilities. Dwindling deposits often caused an equally rapid decline in population, with perhaps a few of the better-financed companies staying on. As time went on a very different type of mining would develop based on the use of heavy machinery and the advice of trained mining engineers and geologists. Eventually, in most areas, the deposits played out, and tourism or ranching replaced the mining.

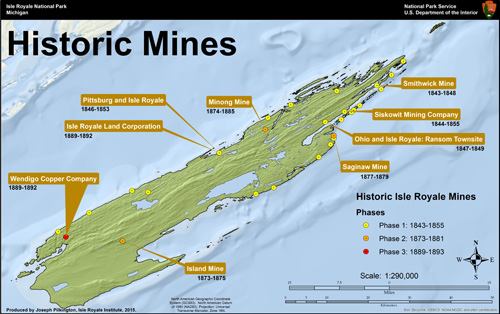

Isle Royale followed this pattern in many ways. There was an early boom-and-bust period, lasting from 1843 to 1855; a lull, and then a revival of mining activity from 1873 to 1881; again a decline, and then a final flurry of mining from 1889 to 1893, ending with a shift to tourism and commercial fishing. Yet Isle Royale is also unique among mining frontiers in several respects. The linking of prehistoric mining with the recent era established a far longer time interval in mining history than on other frontiers; fishing and tourism played a greater and earlier part as supplementary economic activities; and the area, in its final stages, attracted large foreign investment.

Historic Mines

Smithwick Mine | Ohio and Isle Royale | Pittsburg and Isle Royale | Siskowit Mining Company

Minong Company | Island Mining Company | Saginaw Mine | Isle Royale Land Corporation

Wendigo Copper Company

The First Mining Frontier

The first mining explorations on Isle Royale began in 1843, after the Chippewa Indians relinquished claim to the island under a treaty of that year. Previously the only white men living on the island were seasonal fishermen, using the fish houses erected by the American Fur Company between 1837 and 1841. A few mineral locations were filed in 1843 under permit from the War Department; however, the main rush did not begin until 1846, partly because of the more accessible deposits on the mainland, partly because of an erroneous belief that mining rights under the existing mining laws did not extend beyond the south shore of Lake Superior. In 1846, however, a rush began that reached its peak the following year, then rapidly declined and came to an end in 1855. The presence of copper on Isle Royale was a matter of common knowledge by 1843, with information ranging from Jesuit accounts and tales of American Fur Company fishermen to formal geological reports. To this impetus could be added the boom spirit of the time, an abundance of venture capital, and a highly unrealistic estimate of the ease by which fortunes could be acquired through copper mining. One 1846 guide to the mines presented a commonly held belief:

"The cost of getting ore to the surface, on Lake Superior, is about four dollars per ton, one hand being able to get out about half a ton per day. The cost of smelting or washing, so far, is about half that price-say altogether about six dollars per ton. If the ore yield 25% of metal, it is worth, at sixteen cents a pound, eighty dollars; thus leaving a large margin for profits, after paying the expenses of working the mines.Mining operations were carried on by stock companies incorporated in various states-New York, Vermont, Ohio, Michigan, and Illinois were among those represented. At least a dozen such companies had locations on Isle Royale in 1817. The companies varied a great deal-some having professional geologists or mining engineers as agents and advisers, and a respectable amount of capital; others poor in everything except hope and courage; and still others that apparently existed only to sell stock. Prospecting was simplicity itself. A promising fissure or contact vein or dike would be located, sometimes from a boat, sometimes by burning off the vegetation to expose the bedrock. The vein would be followed up, with miners excavating and blasting as they went along, and if the prospects looked promising a shaft would be sunk. As a result, in addition to the established mines, there are hundreds of sites where such explorations are evident. The mining locations were spread around the periphery of the island, like beads on a string, from Malone Bay to Rock Harbor and around to Washington Harbor.

The Miners

Workers were divided into surface men and miners. The surface men worked above ground for wages of about a dollar a day. They cut timber, erected machinery, cleared land, set up tramways, and moved waste rock. Their usual costume consisted of heavy leather boots, canvas trousers, red flannel shirts, and low-crowned, broad-brimmed hats. Of special importance among this group was the blacksmith, whose job it was to sharpen drills and repair metal work.

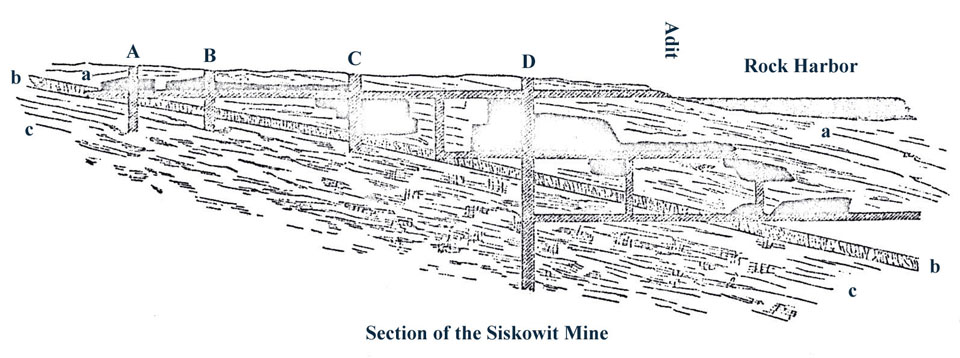

The miners, on the other hand, worked on a contract basis of so much per foot dug. In the Siskowit silver mine at McCargoe Cove, for example, the miners got $20.00 per fathom. Out of this, however, they paid for their supplies-black powder, fuse (at $2.50 for five hundred feet), and tallow candles (15¢ per pound). The drills, however, were sharpened at company expense. In charge of each operation was an agent, or superintendent, who directed surface operations and made contracts and purchases. Below ground a mining captain was boss.

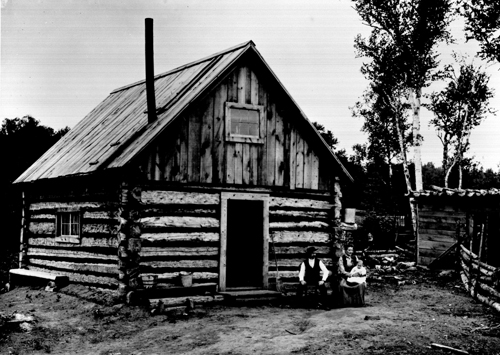

The Richard O'Neils-A mining family at Wendigo. Fisher Collection, 1892, ISRO Archives.

Many of the mining locations consisted of only one or two log cabins. The more substantial settlements-those at Ransom, Siskowit Mine, Snug Harbor, and Todd Harbor-followed a standard pattern. The agent resided in a house of squared logs, while miners lived in crude log cabins. At the Siskowit Mine, in addition, a dozen single workers lived in a combination storehouse and barracks. The grass and vegetation around the settlements was burned to keep accidental fires from destroying the place. Vegetable gardens of potatoes, peas, lettuce, and radishes were grown at Snug Harbor, Ransom, and Siskowit Mine, while the Siskowit operation had extensive hay pastures for their horses. Fish, potatoes, and tea were staples of the miners' diet, supplemented with beef brought in from the mainland.

The sparse population of the island reached a peak of about 120 in the summer of 1847. Most of the men were evacuated each winter, leaving only a skeleton work force.

Life was hazardous, with many injuries and deaths due to drowning, mine accidents, or sheer lack of medical attention. C. G. Shaw in his diary tells of attacks of piles and dysentery, a toothache cured by rather drastic home dentistry, and an accident in which he nearly cut off his great toe. If this weren't enough, he was nearly blinded by bites from mosquitoes and black flies, nagged by the women in camp, and had to put up with insubordination from his Irish workmen! Yet there were compensations. Fishing, rock collecting, and visiting other mines were the chief forms of recreation, and the arrival of the mail boat was always a red-letter day. Trails were built between locations, notably between Ransom and McCargoe Cove, from Siskowit Mine to Malone Bay, from Washington Harbor to Huginnin Cove, and from Huginnin Cove to Todd Harbor. However, most travel was by water.

Mine Operation

Copper mass weighing 6,000 lbs, Minong Mine, NVIC-006, ISRO archives.

Copper was classified in the Lake Superior country in three grades according to its state of occurrence in the rock: "mass," "barrel-work," and "stamp." Masses were large sheets of pure copper occurring in the vein, and weighing from a few hundred pounds to many tons. Smaller masses were taken from the mine intact; larger chunks were divided by means of chiseling. Barrel-work consisted of smaller pieces of copper in bundles and string-like form, bound together with veinstone-the worthless rocky material in the ore bearing vein. With these, as much of the adhering rock as possible was picked free with a hammer, and the copper was barreled up in casks holding from 500 to 800 pounds. Stamp copper consisted of pebble-sized or smaller pieces of metallic copper bound in rock which had to be pulverized by stamping. In this process, the ore was first roasted to make the veinstone friable, so it would yield to the blows of the stamps. The stamp mills consisted of a series of heavy metal shoes, operating from a cam shaft driven by water or steam power. The shoes would crush the ore, and the metal would be separated from the copper through a series of washings.

Most of the copper shipped from Isle Royale-the ore was taken down the lake to Sault Ste. Marie, and thence across to the lower lakes to be smelted-was mass or barrel work. Only two stamp mills operated on the island during this first frontier.

The underground workings consisted of vertical shafts about six feet by eight feet sunk to a suitable depth-generally about sixty feet- where stoping would begin, that is, excavation of the ore made accessible by the shaft. Black powder was used to loosen rock and aid in excavating. The miners, dressed in canvas trousers and stout boots, with candles held on their hard hats by means of a lump of clay, would descend into the mine by ladder, and work an eight or ten hour shift. Rock was hoisted out by means of wooden ore buckets. Hand windlasses were used to hoist the ore to the surface in smaller operations; in the more substantial mines hand work was superseded by horse-powered hoists.

Ventilation and water were the two major problems of mining. The black powder fumes polluted the air, already foul as the shaft grew deeper. To combat this it was a common practice to dig a drift or "winze"-a horizontal tunnel-to another shaft. Water was always troublesome. Where the terrain was favorable, horizontal tunnels (adits) were dug from the surface to connect with the shaft and drain surface water. In the deeper mines steam pumps had to be used.

Most of the mining prospects in the 40's and 50's were short-lived and of little importance. Four, however, are significant. Consult the map, at the top, for locations.

End of the Boom

The mining boom came to an end as rapidly as it had started. By the end of 1847 about half the companies that had been in operation the earlier part of the year were closed. By 1850 only two companies were in operation, and in 1855 the last of these companies closed up. There were a variety of reasons for this collapse of the boom. A change of the mining law, from lease on a royalty basis to sale, was made in 1847, which forced many of the marginal or speculative enterprises to cease operations. The isolation of the island placed it at a disadvantage to the mainland operations. Above all, however, was the fact that the stamp rock on Isle Royale was not very rich in copper, and only by producing masses and barrel work could the mines have prospered.

The Second Mining Frontier

Wendigo Mining Company Headquarters, Washington Harbor, Fisher Collection, ISRO Archives.

The period between 1855 and 1871 was marked by a lull in mining activities. No mines operated during this time, and the island was uninhabited save by fishermen who, during the summer, occupied the old American Fur Company houses in the Siskiwit Bay area and on Fish Island. In summer visitors came over at frequent intervals on vessels ranging from Mackinaw boats to excursion steamers carrying up to 200 passengers. They picnicked in the clover fields at the Siskowit Mine site, fished, and enjoyed the island much as visitors do today.

But the Civil War needs for metal soon caused a rise in the price of copper at a time when national land laws were favorable for speculative buying at low cost. The North American Mineral Land Company-closely connected with the Quincy Mining Company in Hancock, Michigan- began buying up the island, first by use of Connecticut state agricultural college scrip and later by direct purchase at $1.25 an acre. Soon they had purchased 70,000 acres, their holdings including most of the island outside the sandstone belt south of Siskiwit Bay. Their original intention was to revive the operations in the Rock Harbor, Todd Harbor, and Huginnin Cove areas, and to this end they corresponded with former mining captains who had worked in those sites. In 1871 they sent explorers to the island. As a result of their reports three new mining ventures began, one to the north and two on the south side of the island.

In these three undertakings we find much that is common to the second stage of the mining frontier. Trained mining engineers and geologists with a new technique-diamond drilling-supplemented the old haphazard search for outcrops. With more reliable and regular transportation by lake steamer the settlements enjoyed more amenities of life. Schools were established in all the later settlements; physicians and clergymen were represented in the population. The population makeup also changed. Except for the Siskowit Mine which used Cornishmen, the labor force in the earlier mines had been Americans, Germans, or Irish. After 1870, other nationalities appeared, and specialization took place. Cornish miners migrated to Isle Royale, as they did to all parts of the Copper Country, and took over the underground activity. Finns and Norwegians were used as wood crews, and Germans and Irishmen as laborers. The new mining ventures had close financial ties with mining interests on the mainland, particularly with the Quincy interests.

The End of an Era

Historic mining on Isle Royale was a colorful episode in the history of the island. In general, the activity paralleled the story of other mining frontiers in the United States, with its cycles of boom and decline, and, at a later period, in the application of science and technology to the operations. The large foreign investment in the last period of development is typical of the mining frontiers of the far west. In the west, urban centers such as Fort Benton, Spokane, and San Francisco served as supply centers for the isolated mining areas. On Isle Royale, Houghton and Duluth played similar roles, with lake steamers and tugs taking the place of the western freight wagons and pack mules. As in the West a period came in the twentieth century when men found it more profitable to work tourists than ore bodies. The transition of Aspen, Colorado, from a silver mining center to a haven for philosophers and skiers took about forty years. On Isle Royale the transition was more rapid, with the end of the mining era coinciding with the beginning of tourism as a major economic activity.

The Remains Today

Minong Mine Poor Rock, 2013: Minong Mine, Isle Royale National Park.

Visible remains of the fifty years of mining ventures on the island are still plentiful, and most of the sites are accessible by trail. "Poor rock" piles, the debris from shafts and excavations, are evident wherever a mine existed. Closer investigation of the larger mine sites will reveal the eroded foundations of houses, stamp mills, and storehouses.

At Rock Harbor you can see the shaft holes from the old Smithwick Mine along the Moose Trail leading from the Lodge, and a hike of 4 1/2 miles will take you to the largest mine development in the Harbor, the Siskowit site. At Windigo, early exploration trenches are identified along the Windigo Circuit Trail, while decaying log structures dating from the Wendigo Mine operations are within easy hiking distance from the campground.

The two greatest mine developments are inland, but also reached by trails. From the McCargoe Cove Lakeside Camp take the Mine Trail to explore the digging site where 50 men once were employed, and follow the old railroad part way down from the mine. In the same vicinity look for foundations of the long-gone stamp mill, less than a quarter of a mile from the campground on the Chickenbone Lake Trail. Vestiges of the Island Mine are seen along the trail of that name leading off the Greenstone Ridge.

The National Park Service has identified many of these original mining sites, installed interpretive exhibits, and made them available to Park visitors. You may visit these areas but you should remember that structures remaining from the old mining operations are fragile and easily damaged. Their loss would be disastrous to future plans. Look, photograph, and enjoy, but do not disturb.

The timbers of the old shafts and stopes have long since rotted, and the interiors are unsafe. Never enter one of these excavations. Some of the shafts are unmarked and surrounded by undergrowth. Use care in your explorations.

Citations:

- Rakestraw, L., United States., & Isle Royale Natural History Association. (1965). Historic mining on Isle Royale. Houghton, Mich.: Isle Royale Natural History Association in cooperation with the National Park Service.