Panoramic001.jpg)

SS Chester A. Congdon

Quick Facts

Salt Lake City

1907

Chicago Shipbuilding Company

532 feet

6,530 tons

Triple expansion steam engine: 23.5"-38"-65"

Holmes S.S. Co. (W.A. Hawgood)

Continental Steamship Co.

380,000 bushels of wheat

Continental Steamship Co.

James Playfair

Insured for $734,000

U.S. 204526

11/06/1918

$1,500,000

Congdon Shoals on northeast end of Isle Royale

Minimum 50 feet; maximum 200 feet

0

84001716

C

HESTER A. CONGDON was built as SALT LAKE CITY for the Holmes Steamship Company of Cleveland, then managed by W.A. Hawgood. The new steamer was of the 10,000-ton capacity class and measured 532 feet in length, 56 feet in beam with a depth of 26 feet. The gross registered tonnage was 6371.49, and net tonnage was 4,843. While under construction, the Chicago Ship Building Company numbered the hull 74. The steel bulk freighter had 32 telescoping hatches 9 feet wide, on 12-ft. centers, with three compartments of 3,700, 3,100 and 3,400 tons, for a total capacity of 10,200 tons. The ship carried a crew estimated at 19.

The Chicago Ship Building Company departed from its tradition of launching its vessels on Saturdays when SALT LAKE CITY slid down the ways; it splashed into the Calumet River on Thursday, August 29, 1907. The new bulk freighter was given U.S. Registry Number 204526 when it was enrolled September 11, in Cleveland.

The huge, steel bulk freighter was powered by a triple-expansion engine with cylinders of 23.5, 38 and 63 inches on a 42-inch stroke. The engine received its steam from two induced-draft Scotch boilers 14 feet 6 inches x 11 feet 6 inches. Both the engine and boilers were built by the American Shipbuilding Company of Cleveland. The engine produced 1765 indicated horsepower.

Operational History

The first owner of SALT LAKE CITY was the company that had it built: the Holmes Steamship Company of Cleveland, Ohio. The Holmes Company operated the boat until 1911, when it was sold to the Acme Transit Company of Ohio, managed by H.B. Hawgood (May 13, 1911 Certificate of Enrollment).

SS Chester A. Congdon: Patrie Collection, ISRO Archives.

On February 2, 1912, SALT LAKE CITY ownership was transferred to the Continental Steamship Company of Duluth, G.A. Tomlinson, President. A change of name to CHESTER A. CONGDON was registered by D.W. Stocking, Secretary of the Continental Steamship Company, on April 1, 1912. Chester A. Congdon was a prominent Duluth lawyer and financier who had made a fortune in mining and grain interests.

On August 10, 1912, CHESTER A. CONGDON ran aground while waiting for fog to clear. The ship drifted onto a shoal about 4 miles north of Cana Island on Lake Michigan, and damaged several plates (Lake Carriers Association 1913:18; 1912:9).

CONGDON ran aground again in October 1915. The ship was drawing 19 feet 6 inches of water, and it rubbed both bilges hard while going through Grosse Pointe channel during a period of low water. The grounding sheared several rivets, which opened some seams and the vessel began leaking (Bulletin of Lake Carriers Association Nov. 1915:62; May 1915:18).

Wreck Event

CHESTER A. CONGDON aground, Canoe Rocks, 1918. View is from the bow showing the break in the hull aft of the Number 6 hatch. U.S. ACE, Canal Park Marine Museum Collection.

The newspaper that contained the first report of the wreck of CHESTER A. CONGDON carried the news on page 10; the headlines and front pages that day were devoted to the news that World War I had ended (Fort William Daily Times Journal Nov. 7, 1918).

The voyage that would end with one of the most costly marine disasters on the Lakes began on November 6, 1918. At 2:28 a.m. CONGDON left Fort William, Ontario, downbound to Port McNicoll with a cargo of 380,000 bushels of wheat (Lake Carriers Association 1918:142). Other sources list the cargo as 400,000 bushels (Fort William Daily Times Journal Nov. 12, 1918), and 350,000 bushels (Cleveland Plain Dealer, Nov. 8, 1918). The grain had been loaded at the Ogilvie and Pacific elevators ( Fort William Daily Times Journal Nov. 12, 1918). CONGDON had done a 1-day turnaround. The ship arrived on November 5 and cleared downbound on the 6th (Duluth News Tribune Nov. 6, 1918).

CONGDON proceeded a little way past Thunder Cape, where the ship encountered a heavy sea whipped up by a southwest gale. At 4:00 a.m., Capt. Autterson turned his ship and retreated 7 or 8 miles to calmer water, anchoring until 10:15 a.m. By then the wind had abated, although the sea was still running. The captain ventured out again, but after passing Thunder Cape, a thick fog set in. A course was set for Passage Island at 10:40 a.m., and the ship held a speed of 9 knots. The captain's intention was to run for 2.5 hours at that speed and stop if the fog held (Lake Carriers Association 1918:142-143). "I figured on stopping on account of fog until we could locate something. At 8 minutes after 1:00 in the afternoon she fetched up-grounded (from the captain's account, Fort William Daily Times Journal, Nov. 12, 1918).

The ship's officers had not heard the Passage Island fog signal before they struck the southerly reef of Canoe Rocks (Lake Carriers Association 1918:143). Captain Autterson described the events that followed:

We immediately lowered boats and sent one boat over to Passage Island, about 7 miles, to try and secure some assistance from the lighthouse keeper, if possible. We were on Canoe Rocks. Then the second mate took another boat, a fisherman's launch, from Canoe Rocks into Fort William. He had two fishermen with him. The launch became disabled, and they did not reach Fort William until 6:00 Thursday morning (Nov. 7) (Fort William Daily Times Journal Nov. 12, 1918).The second mate brought the first news of the wreck to Fort William. Apparently, CONGDON had no wireless aboard, or it was disabled when the ship struck. The historical accounts indicate no messages were transmitted from CONGDON.

View from the deck of the grounded SS CHESTER A. CONGDON, Canoe Rocks, 1918: U.S. ACE, Canal Park Marine Museum Collection.

As soon as word of the disaster reached Fort William, J. Wolvin, manager of the Canadian Towing and Wrecking Company dispatched the wrecking barge EMPIRE and the tug A.B. CONMEE to the site. The tug SARNIA, with additional equipment, was being prepared to follow soon (Fort William Daily Times Journal , Nov. 7, 1918).

First reports of damage to the stricken ship indicated that the vessel, although damaged, might be saved. "Her forepeak, Nos. 1 and 2 starboard tanks and No. 1 port tank are full of water" (Cleveland Plain Dealer, Nov. 8, 1918). It was hoped that lightering would be all that was necessary to refloat the vessel. The lightered grain was to be placed aboard the barge CRETE (Cleveland Plain Dealer Nov. 9, 1918).

The most serious obstacle to refloating CONGDON would prove to be the weather. When the lightering tugs and barges initially left for the site, the weather had been "calm and thick" (Cleveland Plain Dealer Nov. 8, 1918), but this did not last long. Two days later, by Friday, strong winds had blown up. The crew was removed from the wreck sometime that day, November 8, and was placed aboard the barge EMPIRE. As the wind blew from the southeast at gale force, reaching a speed of 55 miles per hour (Lake Carriers Association 1918:143, Cleveland Plain Dealer Nov. 10, 1918), the crew was sheltered on the barge in protected waters at Isle Royale (Port Arthur Daily Chronicle Nov. 8, 1918).

No loss of life resulted from the wreck. One serious injury, however, did occur before the lightering operations were concluded, due to the fierce gale that drove the salvage vessels and crew to shelter at Isle Royale. Wireless operator Thomas Ives of the barge EMPIRE was transported to the hospital in Port Arthur with a mangled thigh, which was smashed when he caught his leg in a hoisting gear. He was taken to port on one of the attending tugs (Port Arthur Daily Chronicle Nov. 7, 1918).

SS Chester A. Congdon, Canoe Rocks, 1918: Patrie Collection, ISRO Archives.

The messages of the wreck that reached land on November 9 relayed the news that CONGDON had broken in two, and that the stern had sunk in deep water. The tugs had stood by as long as possible, but there was nothing they could do, although they stayed at the site until heavy seas were breaking over the wreck (Fort William Daily Times Journal Nov. 9, 1918). The steamer had broken in two aft of the No. 6 hatch sometime Friday night (Nov. 8th). The forward end remained on the reef in 20 feet of water, but was in very bad condition (Fort William Daily Times Journal Nov. 12, 1918; Lake Carriers Association 1918:143; Cleveland Plain Dealer Nov. 10, 1918). The 36-man crew of CONGDON returned to Fort William, arriving on the tug CONMEE Saturday morning, November 9 (Fort William Daily Times Journal Nov. 12, 1918). The captain, along with Superintendent Close who had arrived from Duluth to investigate the accident, both visited the wreck on Sunday morning and salvaged personal effects from the bow section.

The ship was declared a total loss. The newspapers noted that four-fifths of the cargo would be lost (Fort William Daily Times Journal Nov. 12, 1918). The crew arrived in port in time to participate in the Nov. 11, armistice celebrations. The survivors of the CONGDON wreck paraded in the streets carrying the ship's flag, and a large crowd fell in behind them (Fort William Daily Times Journal Nov. 11, 1918). "We expected to be somewhere on Lake Huron today," said one of the crew, "instead of back again at Fort William" (Fort William Daily Times Journal Nov. 12, 1918).

The wreck of CHESTER A. CONGDON was a tremendous financial loss. When declared a constructive total loss, officials placed the value at more than $1.5 million. Although the owners carried insurance of $365,000 on the hull and $369,400 in disbursements, the wheat cargo alone at $2.35 per bushel was worth $893,000 (Lake Carriers Association 1918:143). Contemporary accounts labeled CONGDON the largest loss ever sustained on the Great Lakes, surpassing the loss of HENRY B. SMITH, wrecked in 1913 (Lake Carriers Association 1918:138; Canadian Railway and Marine World 1918:567; Cleveland Plain Dealer Nov. 10, 1918).

CONGDON's cargo of wheat had been owned by the Wheat Export Company (Canadian Railway and Marine World 1918:567). The lightering operations were only able to remove about one-fifth of the cargo, some 50,000 to 60,000 bushels. The amount remaining was described in the Fort William Daily Times Journal (Nov. 12, 1918):

What it means in wheat-four-fifths of the whole cargo of 400,000 bushels is unsalvageable, meaning a total loss of 320,000 bushels. In money--at $2.24 a bushel, $716,000. In flour- net weight, 97,950 barrels, or 195,900 bags. Made into number 1 pure white flour, allowing 33 percent shrinkage, 100 pounds of wheat equalling about 66 pounds of pure white flour, this four-fifths lost cargo represents 79,200 bushels, or 158,400 bags with a retail flour value of $918,720. In bread-number of standard loaves that could be made from this amount of wheat, 14,139,200 loaves. Allowing 9 inches as the length of a standard loaf of bread, the lost wheat on the CONGDON, if converted into loaves, would reach 6,025.75 miles, or more than twice the distance from Montreal to Vancouver. Computing that one person can subsist on a loaf of bread a day, this amount would be enough to feed the present population of the Dominion for two whole days, or afford sufficient (loaves) for one meal for the whole of the population of Great Britain and Ireland.Shipwreck Site Map

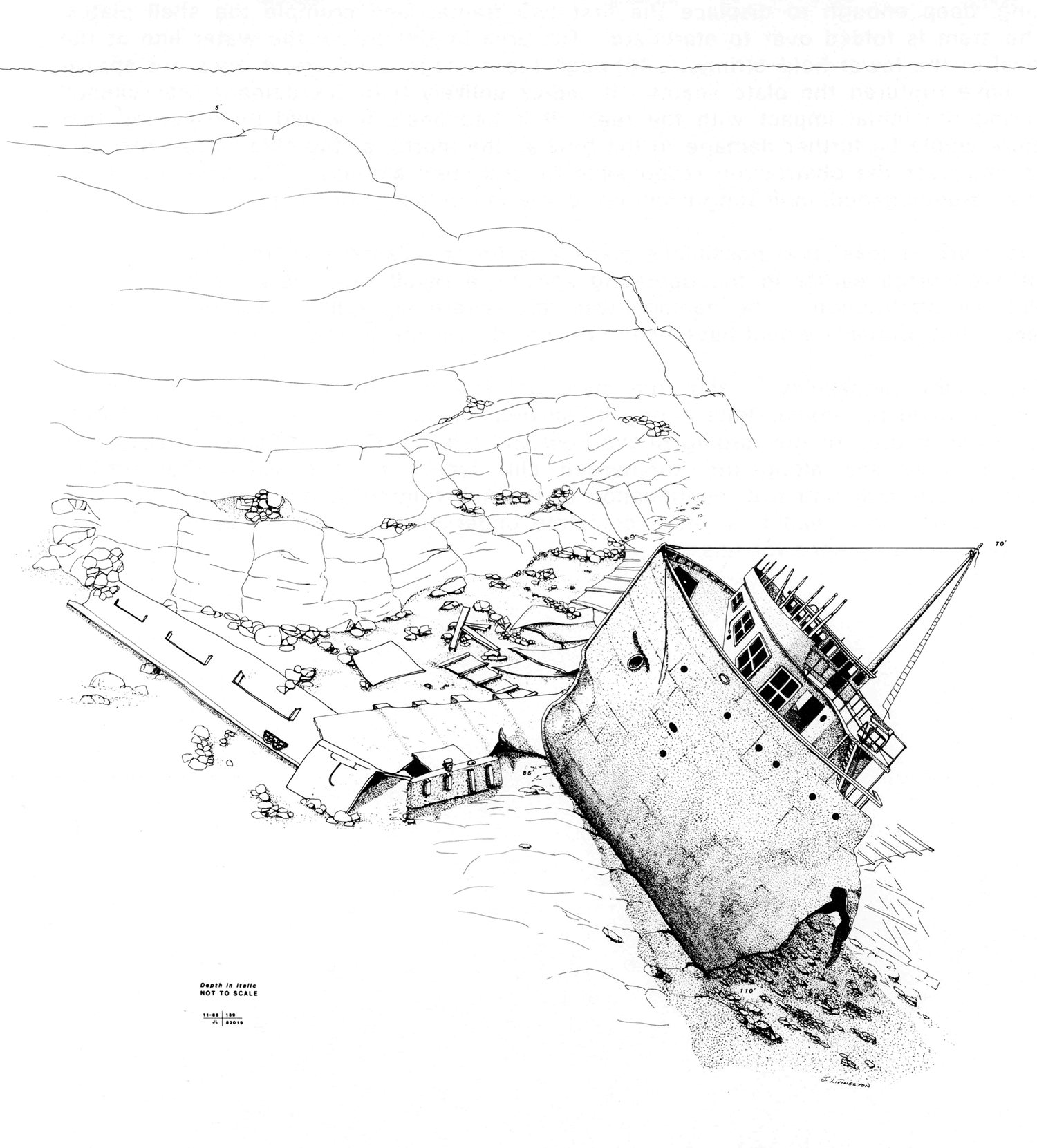

Wreckage consists of intact pilot house and bow section on south side of reef and an intact stern on north side. Much scattered wreckage is found on the reef between these major sections. Buoy on bow, attached at stern in 65 feet.

Hover

SS Congdon Site Map, Submerged Cultural Resource Unit, J.L. Livingston, November 1986, ISRO Archives.

Citations:

- Isle Royale Shipwrecks. December 15, 1965. Isle Royale National Park Archives, Resource Management Records: Branch Chief Era, CRM History (ACC#ISRO-00614, Box 117), Houghton, MI.

- Lenihan, Daniel. Submerged Cultural Resources Study. Santa Fe, N.M: Submerged Cultural Resources Unit, National Park Service, 1987. Print.