Panoramic001.jpg)

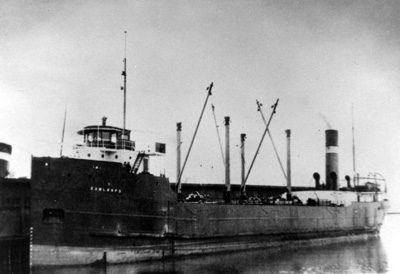

SS Kamloops

Quick Facts

1924

Furness Shipbuilding Company, Ltd.

Furness Shipbuilding Company, Ltd.

250 feet

2,402 tons

Triple Expansion Steam Engine

Canada Steamship Lines, Ltd.

Canada Steamship Lines, Ltd.

William Brian

Papermaking Machinery and Liquor

Canada Steamship Lines, Ltd.

Canada Steamship Lines, Ltd.

Unknown

Canadian 147682

12/07/1927

$2,250,000

Kamloops Point, near 12 o'clock point

Minimum 175 feet; maximum 260 feet

22 (All hands) and 1 diver (2013)

84001769

K

AMLOOPS was built in England by Furness Shipbuilding Co., Ltd. at its shipyard at Haverton Hill on Tees in 1924. Built for Steamships, Ltd. of Montreal, Canada for use in the Great Lakes package trade, the single-screw, steel freighter was designed as a canaler, with dimensions appropriate for passage through the Welland Canal system. Its primary intended function was to transport package freight, but it could also carry bulk cargo.

KAMLOOPS had a length between perpendiculars of 250 feet, molded breadth of 42 3/4 feet and a molded depth of 26 1/2 feet. Its deadweight capacity was 2,400 tons on a 14-ft. draft (Canadian Railway and Marine World July 1924). KAMLOOPS was of the vessel type built to the maximum possible canal dimensions.

A fairly complete description of KAMLOOPS was published in Canadian Railway and Marine World in July 1924 (p. 370):

KAMLOOPS is built on the longitudinal system of framing, with upper, shelter, and forecastle decks. The double bottom, extending all fore and aft, and the peak tanks, are arranged for water ballast, and a water-tight cofferdam is fitted at the sides of [the] fore hold to give added protection to the cargo to meet the severe conditions of the service. The captain's accommodation and chart-room are in house on [the] forecastle deck, with [the] steering wheel in [the] teak Texas house above. Special attention has been given to the accommodation[s] for the officers and crew in [the] forecastle, and engineers and firemen in [the] deck-house aft. The whole of the accommodation is heated by steam radiators, and electric lighting is to be installed. A powerful steam windlass is fitted in [the] forecastle, and special pockets are arranged in the hull to house the anchors. The cargo gear, consisting of 4 sampson posts, each having one 5-ton derrick, is operated by one 8x12-inch and two 7x10-inch steam cargo winches, and mooring arrangements are carried out by means of four 6x10-inch steam mooring winches. A hoisting gear, consisting of 13 winches driven through shafting by a double-cylinder vertical steam engine, will be fitted in the upper 'tween decks for discharging cargo. A steam steering gear will be fitted in [the] after 'tween decks and controlled by shafting from [the] wheelhouse forward and boat deck aft. The propelling machinery consists of a set of triple expansion inverted marine engines, having cylinders of 18, 30, and 50 inches diameter, and a stroke of 36 inches. Steam is supplied by two single-ended boilers 13.6 feet in diameter by 11 feet long, working at a pressure of 185 lbs.

Steamships Ltd., the company that ordered both sister ships built (KAMLOOPS and LETHBRIDGE), was a subsidiary of Canada Steamship Lines, Ltd., and all of its principal company executives were also officers of Canada Steamship Lines. Steamships, Ltd. was incorporated in November 1923, stating its purposes as "to carry on the business of transportation of passengers, freight, etc., towing, wrecking and salvage in or over any of the navigable waters within or bordering on Canada, and to or from any foreign port, and various other businesses connected therewith" (Canadian Railway and Marine World August 1924:422-3).

The first of the two new ships slid down the ways on May 20, 1924, after being christened KAMLOOPS by Agnes Black, daughter of the Canada Steamship Lines superintendent. LETHBRIDGE followed on June 14.

The triple-expansion engine and the Scotch boilers were made specifically for KAMLOOPS by Richardson, Westgarth and Co., Ltd. of Hartlepool, England, and rated at 1,000 indicated horsepower. The engine could push the ship at an estimated speed of 9 1/2 knots.

SS Kamloops: Historic Photograph Collection, ISRO Archives.

KAMLOOPS completed its builder's trial on July 5, 1924 and proceeded to Copenhagen to load the first cargo, which was bound for Montreal. The ship went on to Houghton, Michigan. The vessel, along with its sister, would run regularly between Montreal and Fort William, Ontario carrying package freight west and grain east (Canadian Railway and Marine World Oct. 1924:527).

Operational History

SS Kamloops: Donna Dashney Newmark Collection, ISRO Archives.

KAMLOOPS' first season on the Lakes started late, when its maiden upbound passage began on September 13, 1924 (Detroit Free Press Sept. 14, 1924) under Capt. William Brian and engineer T.W. Verity (Great Lakes Red Book 1925: 51). The new package freighter had arrived from Copenhagen shortly before its sister ship LETHBRIDGE, which reached Montreal on September 18 (Canadian Railway and Marine World Oct. 1924:527). A cargo of pebbles was brought from Denmark for the Calumet and Hecla Mining Company in Calumet, Michigan. Here the crew which sailed on the maiden voyage was replaced by a crew of Lake sailors (Calumet News Aug. 24, 1924; Dec 14, 1927). KAMLOOPS passed Port Colborne on the Welland Canal on September 22 downbound for the first time (Detroit Free Press Sept. 23, 1924).

The first season set the pattern for KAMLOOPS, whose owners continued to operate as long as possible each season. The canaller weathered a severe storm on its last downbound run of the 1924 season on December 13 and 14 when winds of 50 to 60 miles per hour and a temperature of 6° below claimed at least one vessel believed wrecked near Eagle Harbor on the Keewenaw peninsula. After the storm, KAMLOOPS, along with MIDLAND PRINCE, MIDLAND KING AND LETHBRIDGE, each with a load of grain, were all reported downbound on Lake Superior, while other vessels were laid up in the shelter of Isle Royale (Marquette Daily Mining Journal Dec. 15, 1924). The four ships soon became trapped by ice in the St. Mary's River, and two tugs of the Great Lakes Towing Company were dispatched to assist them. Those four vessels were the last of the 1924 season to pass through the locks (Marquette Daily Mining Journal Dec. 17, 1924).

The 1925 season began for KAMLOOPS in April, when it cleared Sault Ste. Marie on the 20th at 3:30 upbound, and again on the 23rd downbound (Detroit Free Press April 21, 23, 1925). In October the freighter was held up with 10 others of the grain fleet during a downbound run by the grounding of W. H. DANIELS in the Welland canal aqueduct (Detroit Free Press Oct 12, 1925). The remainder of the season was uneventful.

KAMLOOPS was technically under new ownership the 1926 season. On October 11, Canada Steamship Lines bought the vessel from Steamships, Ltd. On October 28, 1926 the registry listed a mortgage dated October 19, for $50,000,000 (although the amount seems unlikely) loaned at 6 percent yearly interest by Montreal Trust Company.

The first downbound run of the 1926 season began May 3, when KAMLOOPS cleared Detroit at 3:00 am (Detroit Free Press May 4, 1926). The ship ended its third season like the first - stuck in the ice. This time there were not four ships stuck in the St. Mary's River ice, but more than 100. The 100 ships were caught in the channel near Neebish Island on December 3, the same location where KAMLOOPS had been trapped earlier. That event was the largest ice jam in the history of upper Lakes shipping, according to contemporary references. The soft ice halted all progress of the steamers, and even the powerful tugs made only slow headway through the slush that in places was 12 feet thick. The problem was increased by the fact that there were about 2,000 people aboard the jammed ships, and supplies ran short (Detroit Free Press Dec. 4, 1926).

In a list of vessels freed from the ice on December 10 that was published in the Detroit Free Press (Dec. 11), KAMLOOPS is not mentioned, and therefore must have been released on the 11th after being trapped in the ice for 9 days. It was KAMLOOPS last voyage of the 1926 season.

Wreck Event

The last trip of the 1927 season would be KAMLOOPS' final trip. The doomed vessel cleared Port Colborne, Ontario on the Welland Canal upbound on December 1 at 9:30 AM (Detroit Free Press Dec. 2, 1927). The ship passed Detroit at 11:30. Apparently KAMLOOPS passed through the Soo on December 4 in the company of QUEDOC, a 345-foot bulk freighter (Owen Sound Daily Sun Times Dec. 13, 1927). From Saulte Ste. Marie, Capt. Brian wrote his wife in Toronto, saying that the weather was very bad and that he was going out to anchor his ship (Ibid. Dec. 14, 1927). Mrs. Brian expected her husband home for the winter season six days later on Saturday, December 10.

The giant freeze-up of vessels the year before was still fresh in memory as the 1927 navigation season drew to a close. A rumor had circulated from Buffalo that Lake ships, fearing another blockade, would end their season on November 30, but executives of Canada Steamship Lines denied the rumor. A company official was quoted in the Fort William Daily Times Journal on November 29:

"We will run our ships as long as the weather holds good, and as long as there is grain to carry. The experience we had last year does not deter us because we realize that a thing like that may not happen again for another 50 years." The executive's declaration would prove ironic on two counts: Company vessels would be lost in 1927, and others would end their season icebound in the very same channel as the year before (Detroit Free Press Dec. 15, 16, 1927).

The day following the executive's statement, a 36 mile-an-hour northeast wind began, causing the upbound vessels to shelter overnight on November 30 at Whitefish Point and the Welcome Islands. The temperature was 8°F. at Duluth, 10 F. at Port Arthur, and storm warnings were raised at the Soo. The temperature continued to drop as a massive cold front advanced from the northwest (Sault Daily Star Dec. 1, 1927). This cold front would be closely followed by a worse storm.

The storm increased as the second front arrived, sweeping Lake Superior with high winds on December 5. Upbound vessels, including KAMLOOPS, had been delayed and anchored at Whitefish Bay. The downbound grain fleet had weathered the storm at Fort William. VALCARTIER, the first ship to reach the Soo, arrived heavily laden with a thick coating of ice, and reported temperatures of 40 degrees below during the storm (Sault Daily Star Dec. 6, 1927).

Storm signals were raised once again on December 7, as a northeast wind began blowing at 20 to 30 miles per hour. The temperature dropped to 10 degrees below at Port Arthur. The storm became a major blizzard. The weather remained at sub-zero levels with lows of 10-38 degrees F. below zero reported. The situation on the Lakes grew worse as the storm raged the 7th and 8th. Damage reports began filtering in on the 9th. In all, five vessels were eventually declared a total loss by the underwriters- KAMLOOPS was among the missing.

By December 12, grave concern was mounting regarding the fate of KAMLOOPS, which was now overdue at Ft. Willliam. A search for KAMLOOPS began in earnest December 12. ISLET PRINCE, commanded by A.E. Fader, began searching the north shore (Ft. William Daily Times Journal Dec. 12, 1927). The government tug MURRAY STEWART left from the Soo to join the search (Sarnia Canadian Observer Dec 13, 1927).

Speculation on the whereabouts of KAMLOOPS centered on Isle Royale. Captain R. Simpson of QUEDOC arrived at the Soo and discovered KAMLOOPS still on the unreported list. He gave the following account (Owen Sound Daily Sun Times Dec. 13, 1927):

The QUEDOC passed upbound December 4. Beside her was the KAMLOOPS upbound loaded with package freight, with 21 [sic] men aboard, and captained by William Brian. The QUEDOC was leading and the KAMLOOPS was one-quarter of a mile astern. At ten o'clock Tuesday night [Dec 6], the lookout on the steamer QUEDOC suddenly saw a dark mass ahead, and gave the alarm immediately. The QUEDOC turned sharply to avoid running head on into the rocks at the same time blowing the danger signal to the KAMLOOPS. A north gale was blowing, there was a heavy sea, and it was rough going. The visibility was poor, on account of frost fog, and it is not known if the KAMLOOPS saw the rock or heard the signal. The KAMLOOPS has not been seen or heard of since. She had no wireless aboard.

As more time passed without a trace of wreckage, and hope was reluctantly abandoned, the general feeling grew that KAMLOOPS would remain a Lakes mystery (Sault Daily Star Dec. 14, 1927). The Coast Guard ceased its search of the Keweenaw in the face of heavy seas and ice, and suggested concentrating efforts on the shores of Isle Royale and Manitou Islands (Houghton Daily Mining Gazette Dec. 16, 1927). The ISLET PRINCE, which had seen no wreckage, was called back to port by CSL officials.

Isle Royale and Manitou Island represented the last shred of hope for the searchers. Captain Henry Gehl of the tug CHAMPLAIN believed every bay of Isle Royale should be inspected. "I would like to give the Isle the once-over to be certain. It might be that some member or members of the crew got ashore and are wandering about the island. It must be made certain that no one is on the island before the search for the missing steamer is given up as hopeless" he said (Port Arthur News Chronicle Dec. 16, 1927).

Capt. Gehl was not alone in his belief that survivors might be on Isle Royale. Another tug captain, Sam Wright, said that practically every tug captain, mate and engineer was ready to start a close search of the shore of Isle Royale, and the waters and islands between Port Arthur and the big island, to ascertain the fate of the freighter KAMLOOPS. Wright believed that the missing ship would be found ice-locked on the inner side of Isle Royale between Washington Harbor and Gull Rocks, a stretch of 15 miles of sheer rock where there is no shelter for ships, or else in one of the numerous bays and island-sheltered nooks that extend from Gull Rocks to the outer point of the island (Port Arthur News Chronicle Dec. 17, 1927). The prospect of finding survivors still alive on Isle Royale was considered remote (Daily Mining Journal , Marquette Dec. 16, 1927).

By the beginning of the new year, there was little mention of the loss of KAMLOOPS. In January the Ontario Workman's Compensation Board judged the crew lost and were waiting for receipt of the official report so compensation to the widows and children could begin (Owen Sound Daily Sun Times Jan. 12, 1928; Detroit Free Press Jan. 17, 1928). It was known that there were two women aboard KAMLOOPS during its final voyage. Jennet Grafton and Alice Bettridge were the first and assistant stewardesses. This was to have been the last season on the Lakes for Grafton; it was the second season for 22 year-old Bettridge (Owen Sound Daily Sun Times Jan. 12, 1928).

On May 26, the electrifying news that the fishermen of Isle Royale had found bodies believed to belong to the crew of KAMLOOPS reached the newspapers (Calumet News May 26, 1928; Detroit Free Press May 27, 1928). The cutter CRAWFORD, which postponed entering the drydock in Duluth at Marine Iron and Shipbuilding for repairs, went to investigate. Two bodies had been reported found by David Lind (Duluth News Tribune May 27, 1928).

The bodies, both wearing life preservers with "KAMLOOPS" stenciled on them, were reported located near Twelve 0' Clock Point on Amygdaloid Island (sic) on the north shore of Isle Royale. They were found along with wreckage of the lost steamer. Fragments of superstructure, including the top of the wheelhouse, a spar with a flag on which was printed KAMLOOPS, and a lifeboat were found in the area between Green Isle and Hawk Island. Captain. Christianson stated that the wreckage includes all of the boat's hatches, half a lifeboat and five or six pairs of oars. The beach is covered with medicine, candy, tooth paste, and foodstuff carried by the steamer. The reason the steamer was not found until Saturday was because ice on the little bays is just beginning to melt. Indications are that the steamer KAMLOOPS can not be very far from Isle Royale (Duluth News Tribune May 28, 1928).

On June 4, six more bodies of KAMLOOPS' crew were found, again by fishermen. News of the discovery was relayed to the port cities from Isle Royale by the captain of WINYAH. The bodies were decomposed, but one appeared to be that of a woman (The Calumet News June 5, 1928).

At first, the woman, reportedly found attired in nightclothes, was believed to be stewardess Netty Grafton of Southampton (Owen Sound Daily Sun Times June 6, 1928). The woman was later identified as Alice Bettridge, the assistant stewardess, an identification based on the fact that the body had a set of natural teeth; it was known that Netty Grafton had false teeth (Port Arthur News Chronicle June 7, 1928). The report that Bettridge was found in her nightclothes was denied. Brock Batten stated, "She was fully dressed and wore a sweater and a coat (Ft. William Daily Times Journal June 7, 1928). This evidence supports the belief held at the time by many that the bodies found were the occupants of a lifeboat that made it to shore. All had been found with lifebelts.

A ninth body was found inland some distance from shore, believed to be the remains of Honore (Henry) Genest, first mate. The body had no lifebelt, although one was found in the vicinity. It was surmised that the first mate was able to make it to shore and remove his lifebelt before succumbing to the elements (Ft. William Daily Times Journal June 14, 1928).

Discovery of The KAMLOOPS

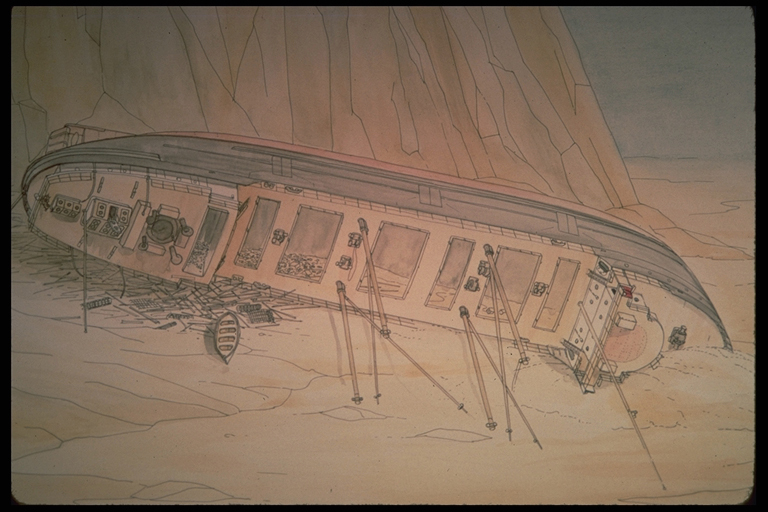

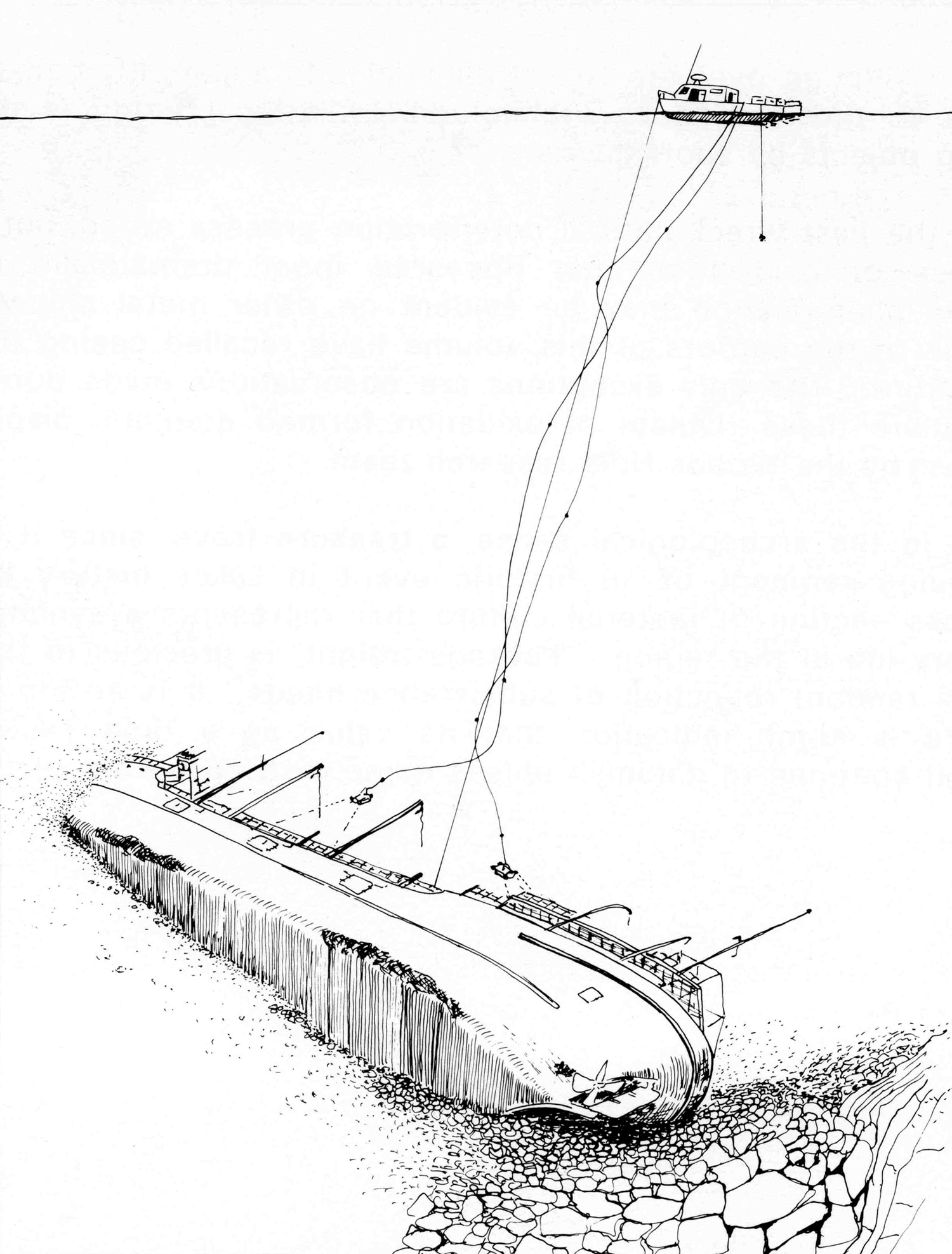

Diagram of the SS Kamloops: Diagram courtesy of the National Park Service website.

The location of KAMLOOPS remained one of the mysteries of Lake Superior until August 21, 1977. On that date Minneapolis sport diver Ken Engelbrecht spotted the dark shadow of the wreck during an exploratory dive searching for KAMLOOPS. Engelbreht, along with dive partner Randy Saulter of Mounds View, was carrying out a systematic search in the area known as Twelve O'Clock Point. The dive team had been directed to the possible site of the wreck by Roy Oberg, captain of the VOYAGEUR II. Oberg had made a fathometer tracing several years earlier in the area that indicated a shipwreck lying on its side (Press release by Ken Engelbrecht and Thorn Holden, 1977).

The wreck was found while diving off Ken Merryman's boat HEYBOY, on the second day of the search. On earlier dives, bits of cargo, such as a brass barrel and a ladder, were sighted. Then, "enough pipe to fill a semi-truck." On the last dive of the weekend, Engelbrecht, at a depth of 195 feet "saw this really big shadow, the KAMLOOPS, and this other shadow coming out of it, which was the flagpole. I got a really big rush and started trucking over there" (Minneapolis Star Oct. 13, 1977).

The next dives on the wreck were done September 5 and 6, 1977, but there was some doubt that the wreck was indeed KAMLOOPS. The real proof, he [Ken Merryman] said, came after the second dive when pictures, on close inspection, showed the ship's name peeking out through the years of accumulated rust and underwater debris on the freighter's stern ...

Later dives by those and other divers add to what is known of the last moments of KAMLOOPS. A party led by John Steele filmed the wreck in 1978. This expedition discovered that the engine telegraph was set at the "Finished With Engines" position, indicating the engines may not have been operational at the time of sinking, or that the vessel was laid to before the disaster. Steele's party made the following speculations based on their observations:

In the position of her last sighting and in the raging storm, a guy wire attached to the port side of KAMLOOPS' stack snapped or tore free. The stack, no longer secure and positioned only by gravity, toppled to the starboard side shearing off the ventilators and crashing overboard breaking through the starboard railing atop the stern cabin. The coal fired, forced draft engine could not function without the stack. The crew was forced to "finish" the engines. If there had been power available, they would have been put on "Standby" not "Finished With Engines." KAMLOOPS' power plant was shut down before she sank. With no power, she was at the mercy of the raging storm and the northeast gales tossed and blew her toward Isle Royale.

She hit Isle Royale broadside, smashing her starboard bow. Temporarily, she remained fixed on the reef, quickly taking on water she rapidly sank bow first to rest at the foot of the reef. The crew probably thought themselves safer aboard rather than facing the icy seas and sub-zero temperatures. They probably hoped she would remain foundered on the reef, leaving a potential for rescue. However, the opened cabin door may indicate a hasty departure of crew members as they realized their doom .... The other twelve crew members probably remain trapped in the stern house, yet to be opened (Schuette 1979:41).

Shipwreck Site Map

Intact and undisturbed. Diving not advised because of extreme depth. Not buoyed.

Hover

SS Kamlopps Site Map, Submerged Cultural Resource Unit, ISRO Archives.

Citations:

- Isle Royale Shipwrecks. December 15, 1965. Isle Royale National Park Archives, Resource Management Records: Branch Chief Era, CRM History (ACC#ISRO-00614, Box 117), Houghton, MI.

- Lenihan, Daniel. Submerged Cultural Resources Study. Santa Fe, N.M: Submerged Cultural Resources Unit, National Park Service, 1987. Print.