Panoramic001.jpg)

SS Emperor

Quick Facts

1910

Collingwood Shipbuilding Co.

Collingwood Shipbuilding Co.

525 feet

10,000 tons

Triple Expansion Steam Engine

Inland Lines, Ltd.

Canada Steamship Lines, Ltd.

Eldon Walkinshaw

10,429 tons of iron ore

Canada Steamship Lines, Ltd.

Canada Steamship Lines, Ltd.

Unknown

Canadian 126654

6/04/1947

North side of Canoe Rocks

Minimum 25 feet; maximum 175 feet

12

84001748

W

hen the steel bulk freighter EMPEROR was launched on December 17, 1910 (Port Arthur Daily News April 8, 1911), it was the largest ship ever built in Canada (Duluth News Tribune April 9, 1911). It was built as hull number 28 by the Collingwood Shipbuilding Co. of Collingwood, Ontario, for James Playfair's company, the Inland Lines Ltd. of Midland, Ontario. Playfair would eventually build up a substantial fleet of Lakes carriers, and EMPEROR was his first large vessel. Evidently Playfair had a penchant for giving his ships names that related to royalty, for in later years he would own vessels with names like EMPRESS OF MIDLAND, EMPRESS OF FORT WILLIAM and MIDLAND KING (Greenwood 1978:53).

The length of EMPEROR was 525 feet, breadth 56.1 feet, and depth 27 feet. Molded depth was 31 feet and the draft could go as deep as 27 feet. The gross tonnage was 7,031 and the registered tonnage was 4,641. The original registry number assigned to the vessel at its home port of Midland was 126654. The Transcript of Register states EMPEROR had one deck, two masts, was schooner-rigged with a plumb bow and elliptical stern.

The new ship was built of steel and designed on the arch-and-web frame system of construction to create an unobstructed cargo hold under the 30 hatches. Each of the hatches was 9x36 feet wide and placed on 12-foot centers. There was an ore chute at each hatchway (Railway and Marine World Jan. 1911:89). The ship had 11 bulkheads; the engine room was 67 feet long.

EMPEROR was powered by an inverted, triple-expansion steam engine built by the Collingwood Shipbuilding Company. The engine had cylinders of 23, 38.5 and 63 inches on a 42-inch stroke, and received steam at 180 pounds of pressure from two Scotch boilers 15.5 feet in diameter and 12 feet in length. The engine produced an indicated horsepower of 1,500 (Transcript of Register) at 82 revolutions per minute. Registered nominal speed was 10 knots. By the time the vessel sank, its normal speed loaded was 11 knots.

Operational History

SS Emperor: Historic Photograph Collection, ISRO Archives.

EMPEROR was launched December 17, 1910, but was not ready to go into commission until April 1911 (Port Arthur Daily News April 8, 1911). By the time the ship was ready for its first trip, the captain selected was G.W. Pearson, and G. Smith was chosen to be the chief engineer for the season (Canadian Railway and Marine World March 1911:283).

The huge bulk carrier's first season commenced with a major incident. The ship broke its main shaft in Thunder Bay, Lake Huron, and was towed to Detour, Michigan (Canadian Railway and Marine World June 1911:573; Port Arthur Daily News May 26, 1911).

The broken shaft on the first trip out was not the most serious mishap to befall EMPEROR during its first season. While anchoring in the Canadian canal at Sault Ste. Marie, the ship rode over its anchor, causing it to tear a hole in the bow. The freighter sank the few feet to the bottom blocking the channel. It was released, and after temporary repairs were made, proceeded on to Midland, Ontario (Canadian Railway and Marine World Nov. 1911:1085).

In May 1916, James Playfair sold EMPEROR to the Canada Steamship Lines Ltd. of Montreal, Quebec. Playfair was listed as the sole owner of the 64 shares of the ship (Transcript of Register).

Another incident occurred October 29, 1926, when EMPEROR was grounded on Major Shoal near Mackinaw City, Michigan. The ship was released unharmed at 4:00 that afternoon after jettisoning 900 tons of ore (Detroit Free Press Oct. 27, 1926). It is not known how EMPEROR dumped the ore.

In 1936, EMPEROR lost a rudder (Toronto Evening Telegram June 4, 1947). A man was washed overboard at the same time. EMPEROR ran aground in 1937 off Bronte, on Lake Ontario, and was soon released (Toronto Evening Telegram June 4, 1947.

Wreck Event

SS Emperor mast, Canoe Rocks, 1947: McPherren Collection, ISRO Archives.

EMPEROR struck Canoe Rocks off Isle Royale June 4, 1947 and sank in about 30 minutes. Three officers and nine crew were lost. The following account was developed from the official investigation of the disaster conducted by Canadian officials on June 6 and July 2 and 3, 1947:

EMPEROR had brought up a load of coal and unloaded at the coal docks at Ft. William. The freighter had immediately moved from the coal docks to the Port Arthur Iron Ore Dock to load ore. The loading of ore took six to seven hours. The first mate had supervised the loading and took the watch after they cleared the breakwall.

The doomed ship was laden with 10,429 tons of bulk iron ore (removed from the Steep Rock Mine) stowed in its five holds when she cleared Port Arthur at 10:55 p.m., June 3, downbound for Ashtabula, Ohio. The steamer was in seaworthy condition and well-equipped with suitable charts and sailing directions for the intended voyage. EMPEROR was also carrying a gyro compass, echo meter, sounding machine, ship-to-ship and ship-to-shore telephone and the "latest modern type of Marconi direction-finding equipment," in addition to the usual compasses and other equipment. EMPEROR, however, did not carry a full crew. There was no third mate.

The weather was good, the wind light and visibility excellent. These favorable conditions held for the short voyage. The navigation lights of Passage Light and Blake Point should have been clearly visible. Passage Island Light should have been visible from Trowbridge Light outside Thunder Cape, and Blake Point Light should have been visible for at least an hour before the wreck occurred.

Chief Engineer Merritt Dedman, a 63-year-old veteran of 32 years on the Great Lakes, was awakened when the ship struck and told the following story to the press:

"I didn't have to have anyone tell me something seriously was wrong. I threw on my clothes and went down to the engine room. I listened as I ran down a passage. The engine started to race and I knew then that the propeller was gone. It was a case of waiting with our fingers crossed until the captain gave the order to abandon ship. He wasn't long; about 10 minutes, I would say. (Dedman got into the starboard lifeboat and found himself up to his knees in water.) We picked up several men in the water and cruised around until we were picked up by the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter (Port Arthur News Chronicle June 4, 1947)."

The watch sequence established that Capt. Eldon Walkinshaw had the watch until midnight when the first mate, James Morrey, took over. He had the watch from midnight to 6:00 a.m., and spent that time seated in a chair in the front of the wheelhouse. Evidence brought out that Morrey was in charge of loading the vessel in port before departure during most of the 6 hours he normally would have been off duty and, as a result, was probably overtired during his watch and fell asleep.

According to the testimony of J. Leonard, wheelsman, who was on duty the watch before the accident, the courses were plotted by the first mate at Thunder Cape. The course steered from Welcome Islands to Thunder Cape was 138 degrees true with a 2 degree alteration to pass the steamer BATTLEFORD. Leonard, who was inexperienced in the upper Lake region (this was his first time steering downbound from the Lakehead), believed the course was altered to 98 degrees true abreast of Trowbridge light. The mate did not take a four-point bearing, a bearing on the light, nor did he use the radio beacon on Passage Light. Leonard went off watch at 4:00 and stated Passage Island Light was 10° off the port bow. He turned the wheel over to J. Prokup. The mate did not check the course at the watch change.

Peter Craven, the second mate, related his experiences during the sinking:

"As the ship began to list sharply the captain gave his abandon ship order. The first boat was lowered and floated without too much trouble and men piled down ropes to get in while others jumped into the water. I jumped in and managed to get in the second boat but she was capsized by suction of the sinking ship. Most of the missing were in or about this second boat. Down we went When I came up I reached the surface a moment before the boat came up overturned. (He climbed on the boat with Louis Gale and Ed Brown.) We were a wet, cold bunch as we waited for the rescue ship to reach us. I'm still shivering. Gee, that water was cold (Port Arthur News Chronicle June 4, 1947)."

There was no record of the ship's course until it passed Welcome Island at the mouth of Thunder Bay. At Thunder Cape Light, the normal downbound course should have been set to 98 degrees true; however, the court determined that the course was not set until the ship was abreast of Trowbridge Light, some 3 miles beyond Thunder Cape Light.

EMPEROR struck Canoe Rocks shortly before 4:15 a.m. According to various accounts, the ship stayed afloat from 20 to 35 minutes.

Two lifeboats were launched, one from each side of the ship, but both ran into difficulties. The one on the starboard side lost a bilge plug, and when the 10 sailors aboard were rescued, they were knee-deep in water. The port lifeboat pulled away from the wreck but was sucked under by the ship when it went down. Four men were clinging to it when the 125-foot, 250-ton cutter KIMBALL arrived, which had been in the vicinity of Isle Royale repairing navigation lights. The suction from the sinking ship also pulled crew members below the icy waters-some said they had been drawn down 30 to 40 feet as the freighter sank. Second Mate Peter Craven of Port McNicoll, Ontario said he was pulled under twice by the suction (Winnipeg Free Press June 4, 1947).

SS Emperor Pilothouse, Canoe Rocks, 1947: Historic Photograph Collection, ISRO Archives.

Soon after the cutter arrived, the survivors began to relate stories of their grim struggle. There had been no panic after the ship struck. Eleven of the crew were still missing, including the captain, who was last seen on the bridge of his wrecked ship (Winnipeg Free Press June 4, 1947).

KIMBALL picked up 21 survivors and the body of the first cook, Evelyn Shultz, of Owen Sound, Ontario. The survivors were brought to the Fort William City Dock on the Kaministiquia River at 8:30 a.m. The company gave each wreck survivor $100 for clothes and essentials. The survivors were transported to EMPEROR's downbound destination aboard a Canadian Pacific Railway sleeping car provided by Canada Steamship Lines.

When KIMBALL left the site with the survivors, the only trace of the ship above the water was the mast jutting some 15 feet above (Minneapolis Star June 4, 1947). However, pictures taken after the wreck show the top of the pilothouse was exposed.

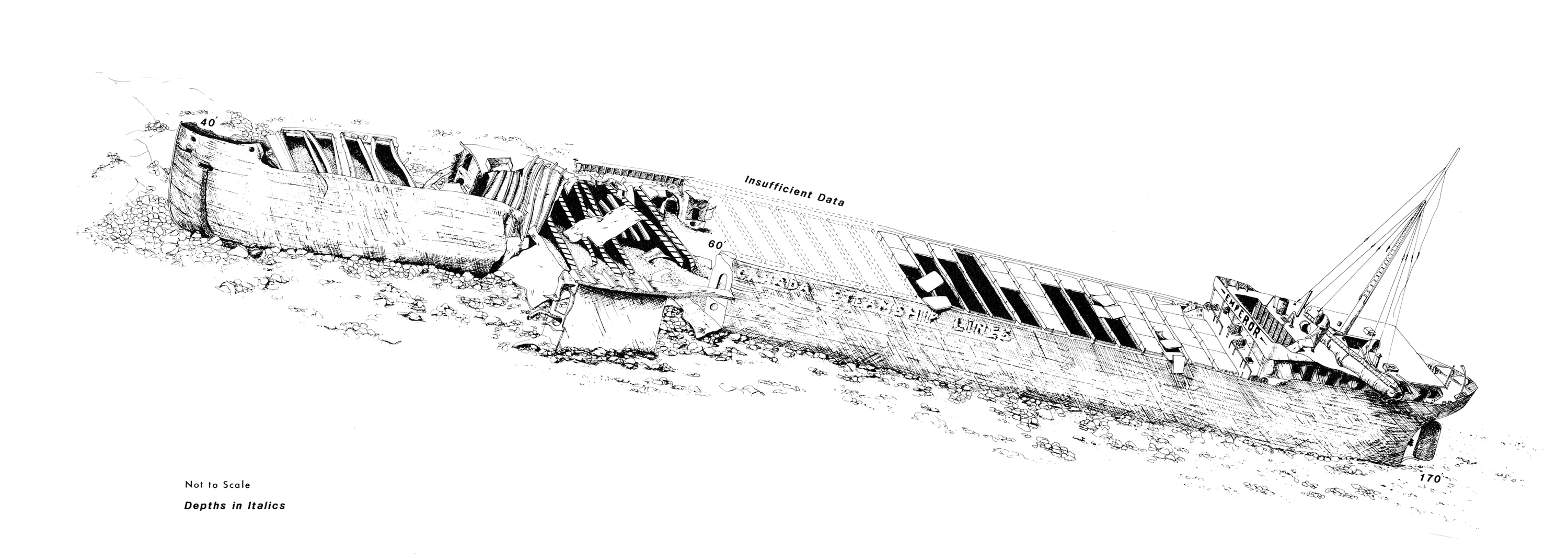

Shipwreck Site Map

The wreck is basically intact, with the bow area showing most damage. Stern area features an intact mast rudder/prop, engine room, and numerous cabins. Buoy on bow attached at stern in 25 feet; buoy on stern attached on deck at 100 feet.

Hover

SS Emperor Site Map, J.L. Livingston: Submerged Cultural Resource Unit, ISRO Archives.

Citations:

- Isle Royale Shipwrecks. December 15, 1965. Isle Royale National Park Archives, Resource Management Records: Branch Chief Era, CRM History (ACC#ISRO-00614, Box 117), Houghton, MI.

- Lenihan, Daniel. Submerged Cultural Resources Study. Santa Fe, N.M: Submerged Cultural Resources Unit, National Park Service, 1987. Print.