19th Century

By: Caven Clark

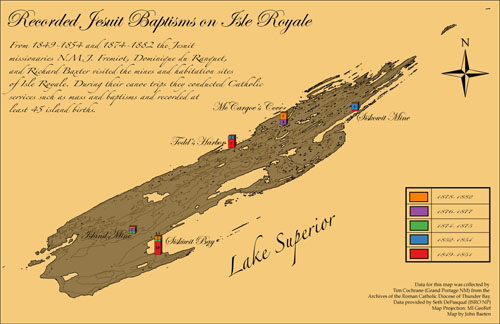

ineteenth-century documentation clearly indicates that an aboriginal population that included Ojibwa, Cree, and Assiniboin groups was present on the north shore of Lake Superior in the area of the "Great Carrying Place" (Grand Portage) and near the mouth of the Kaministiquia River at Fort William (present day Thunder Bay, Ontario). From the last quarter of the eighteenth century into the first half of the nineteenth century the depots of the North West Company and (after the merger in 1821) the Hudson's Bay Company at this location served as cultural and economic centers for the surrounding region for Euroamericans and Native Americans alike.

The use of Isle Royale's resources by native groups was nonintensive, consisting mainly of hunting and fishing by small single or multifamily groups originating from the north shore. The native and Metis population remaining at Grand Portage continued to exploit the island's resources. After 1836, when the American Fur Company (AFC) expanded its operations to include commercial fishing, were much sought after for their knowledge and expertise in the local fishery (Cochrane n.d.). Ojibwa men and women were employed by the AFC; the men engaged in fishing, and the women processed the catch. Most of the AFC fishing establishments on Isle Royale coincided with prior aboriginal sites and, after the termination of AFC fishing in 1841, these sites were subsequently reoccupied as seasonal sites by native groups. The Treaty of LaPointe (1842 and 1844) ceded Isle Royale to the US. Government, altering but not eliminating native interests in Isle Royale.

There is sketchy evidence for a trading post of the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) on the island at Hay Bay although there is no clear documentation in support of this. A.C. Lane's (1898) geological report, which referred to an HBC establishment at this location, seems to be the basis for the persistence of the tradition. This location could not be further clarified through field survey or by archival research.

Ives reported the location of an Indian maple sugaring camp on Red Oak Ridge or Sugar Mountain near the Island Mine. Sarah Barr Christian's diary relates a trip she made to a sugaring camp "on the north side of the island" (Christian 1932). The identification of historic period aboriginal sites poses special problems. The almost wholesale adoption of goods of non- native manufacture renders the occupation and resource, utilization sites of Native Americans nearly invisible archeologically. Differences in fish processing techniques, where heads and tails are left with the body, may be a clue to an aboriginal site. But in most instances this distinction will be very difficult to support empirically.

With the legal cession of land to the United States Government in 1842, Isle Royale underwent the surveying necessary for its ultimate disposition to various mining concerns (e.g., Ives 1847). As Ives was gridding out the island, prospecting and mine openings were already underway. The first rush for copper began in 1846 but was nearly played out by 1850, the Siskowit Mine closing in 1855. Following the Civil War an increase in the price of copper caused a second rush, beginning in 1871.

It was during this period that the Minong and Island mines were opened. But the rush was, like the first, short lived, with most mines closed by 1879. A final attempt to extract a profit in copper was made in 1889-1890 by the Wendigo Company, but it too was forced to abandon its operations by 1892 (Rakestraw l967a).

Archaeological Survey, 2014

By: Seth DePasqual

Archaeologists discovered this iron offset awl (pictured below) during a 2014 survey of a Native American (Anishinaabeg) sugar bush camp near Island Mine. The awl was a ubiquitous item within an Anishinaabeg toolkit, and would have been used to punch holes in birch bark while crafting canoes or sap buckets. The offset (or lightning-bolt) design prevented breakage during use. The age of this awl is unknown, but it could have been used as early as 1847 when surveyor William Ives recorded the sugar bush camp above what would later become the Island Mine. Later, in the 1870s, workers and families associated with the Island Mine operation interacted with Anishinaabeg peoples as they made their way up to the sugar bush.

Citations

- Christian, Sarah. 1932. Winter on Isle Royale, A Narrative of Life on Isle Royale During the Years of 1874 and 1875. Non-dissertation manuscript, University Microfilms International, Ann Arbor.

- Clark, Caven P. Archeological Survey and Testing at Isle Royale National Park, 1987-1990 Seasons. Lincoln, Neb: U.S. National Park Service, Midwest Archeological Center, 1995. Print.

- Cochrane, Timothy. n.d. Ojibwa Fishing Skills and the American Fur Company's Fishing Experiment on Lake Superior. Manuscript on file, Isle Royale National Park, Houghton.

- Ives, William. 1847. Land Survey Notes and Plats of Isle Royale, Michigan. Files of U.S. Bureau of Land Management, Washington, D.C.

- Lane, A.C. 1898. Geological Report on Isle Royale. Michigan Geological Survey 6(1). Lansing.

- Rakestraw, Lawrence. 1967a. Post Columbian History of Isle Royale, Part I, Mining. Manuscript on file, Isle Royale National Park, Houghton.